“Legacy modernization” the updating and optimization of aging core systems has become a critical priority for many companies. Yet in practice, modernization efforts often encounter obstacles and fail to progress as planned. Drawing on NRI’s field insights, this article outlines the three major challenges that commonly hinder modernization and explains practical approaches to overcoming them.

Chapter 1: Current State of Legacy Modernization and Its Challenges

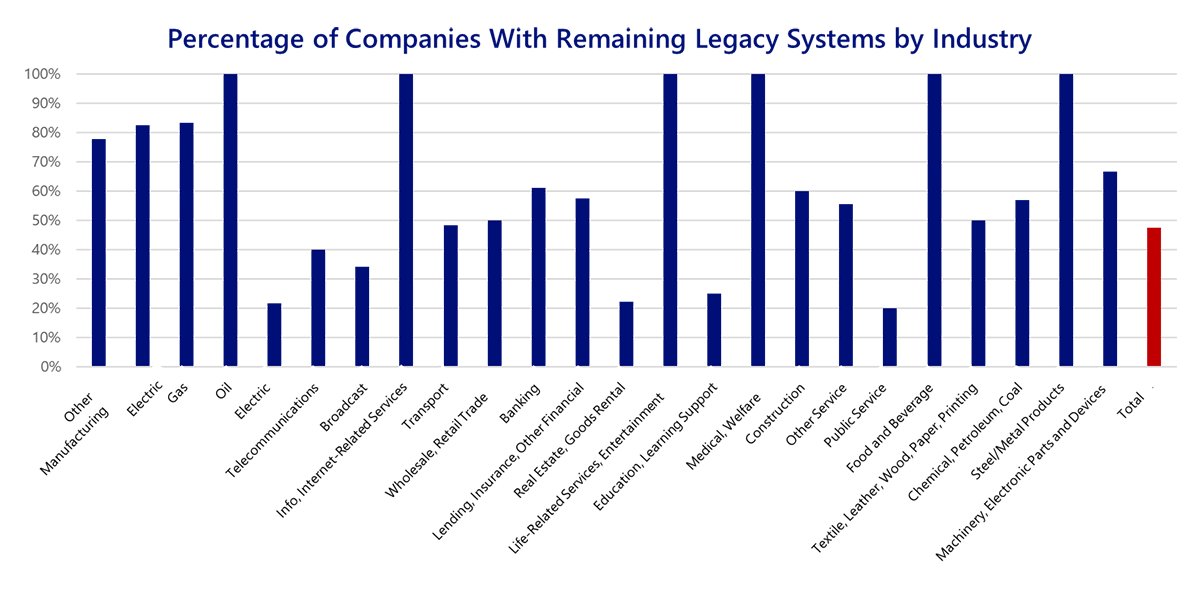

Many companies in Japan have focused on legacy modernization since the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry first warned of the 2025 Digital Cliff in its 2018 DX Report. The 2025 Digital Cliff refers to the sharp decline in competitiveness that could occur if companies continue relying on outdated systems that become too costly, risky or complex to maintain. Yet even now, across nearly all industries in Japan, a high proportion of companies still retain legacy systems, with many sectors exceeding 70 percent and some approaching or reaching almost full reliance. (Chart 1)

Chart 1: Percentage of Companies with Remaining Legacy Systems by Industry Sector

Source: IPA 2024 Software Trends Survey Results

Why is progress so slow? Once companies begin, they encounter challenges they had not fully anticipated. In one manufacturing company, for example, a global core system that had run for many years had become outdated, making it difficult to secure maintenance personnel and increasing the risk of the system turning into a black box with unclear inner workings. Although the company launched a project to overhaul the system, it struggled to build consensus among stakeholders, leading to repeated revisions. Several years later, the project remains stuck at the current state assessment and conceptual planning stage. In many companies, similar efforts stall or are abandoned partway through.

These challenges are widespread. Broadly, three barriers hinder legacy modernization. The first is gaining alignment with stakeholders. The second is conducting an accurate current analysis. The third is managing the project effectively.

Chapter 2: Three Challenges of Legacy Modernization and How to Address Them

1. Gaining Alignment with Stakeholders

Legacy modernization is often initiated by IT departments that recognize the urgency of the issue. However, management and business departments frequently lack a comparable sense of crisis. Many feel that the cost and effort of modernization are not justified, which leads to limited cooperation and stalled projects.

IT investments are typically evaluated based on cost effectiveness, but legacy modernization is driven primarily by risk avoidance. Recovering the investment through measurable impact is difficult, especially for back-office systems such as accounting and human resources that have a limited number of users. This makes it challenging to communicate quantitative benefits.

It is therefore essential to establish alignment with management and business departments by framing modernization as an investment in cost versus risk reduction, while also highlighting potential additional benefits.

Risk |

Benefits |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In many real cases, companies pursue legacy modernization primarily for risk avoidance. Clarifying the purpose of legacy renewal and managing costs are both essential. With the recent rise of powerful yet inexpensive packages and SaaS products, many companies are now considering these options to keep modernization costs under control.

2. Conducting Accurate Current Analysis

When organizing requirements for a new system during legacy modernization, current functional requirements are sometimes overlooked. This often happens because neither the business department nor the IT department fully understands the origins of past requirements, the details of existing specifications or even whether those specifications are still necessary.

As a result, new systems are designed solely around the ideal ToBe vision without a full grasp of current operations or the actual state of the existing system. During construction phase, gaps or omissions in the current specifications surface, causing the development scope to expand and leading to cost and schedule overruns.

This is why starting with current analysis is essential. When systems are relatively small, design documents are up to date and experts familiar with the current specifications are available, the analysis can be carried out by reviewing existing documents and interviewing specialists.

However, with older legacy systems, design documents may not exist, may be outdated or there may be no one, either in house or at the vendor, who understands them. In large scale development environments, even existing documents can be difficult to decipher, a challenge that also arises when packages include extensive additional development.

To address these challenges, companies are increasingly turning to AI tools that analyze source code and regenerate design documents, with supported document types and languages continuing to expand. After visualizing the current system, AI can also provide proposals for system division based on system connections and program complexity, although human judgment remains essential to validate and refine these insights.

3. Managing the Project Effectively

Legacy modernization projects are often difficult to manage due to their large scale and the number of people involved. Long construction periods also increase the likelihood that changing business conditions will affect requirements, making them harder to control. To mitigate these issues and manage effectively, it is important to set project size in increments that are appropriate for project managers to oversee.

Past examples show that when the scope assigned to each project manager is set at a manageable scale, such as by business unit, subsystem or a defined development size, managers are better able to grasp the whole picture and manage quality and progress appropriately. Working on multiple divided areas in parallel can also help prevent projects from becoming prolonged and allows companies to see results earlier. However, while simultaneous work offers clear advantages, it introduces greater complexity and requires proper measures.

When promoting a large-scale project across several areas, inconsistencies in interfaces and specifications can cause major issues. In one major manufacturing company, a large core system upgrade experienced significant post go-live problems due to such inconsistencies, which had a serious impact on business operations.

To avoid these risks, several points are essential when working across multiple areas. First, from an organizational standpoint, a general project manager should be appointed to oversee QCD for the entire project and make cross functional decisions. Because this role cannot directly intervene in every discipline, it is critical to establish structures and systems, such as unified project management tools and reporting rules, that allow visibility into each area from the outside.

In planning tasks and schedules, it is also necessary to clarify the points where areas intersect and where they can proceed independently, ensuring consistency across the overall plan. Additionally, tasks that secure the feasibility of the entire business and system—such as walkthroughs after requirements definition, overall migration policies and plans, and overall testing policies and plans—must be defined in a way that aligns content across all areas.

By implementing these measures, it becomes possible to execute large scale modernization projects through the simultaneous advancement of multiple areas.

Chapter 3: Conclusion

Legacy modernization is complex by nature. Projects stall not because companies lack intent, but because they face three persistent obstacles: difficulty aligning stakeholders, difficulty understanding current systems and difficulty managing large scale projects. By clarifying the purpose of modernization, conducting thorough current analysis supported by AI tools and structuring projects in manageable, well-coordinated units, companies can avoid common pitfalls and move modernization forward with confidence. With the right approach and governance, even large-scale initiatives can progress smoothly and deliver meaningful results.

Profile

-

Ryota UzuPortraits of Ryota Uzu

IT Consulting Department for Industrial-Sector I

Joined NRI in 2009. Specializes in system consulting services, including business process transformation planning, IT strategy and system planning, and management support for large-scale system development projects.

In recent years, focuses on CDO/CIO agendas such as digital organizational transformation, digital-driven business and operational innovation, and legacy modernization, supporting transformation initiatives in the manufacturing industry and related sectors.

-

Hirokazu WatanabePortraits of Hirokazu Watanabe

IT Consulting Department for Industrial-Sector I

Joined NRI in 2016. Experiences in consulting services for core system planning and implementation, mainly in the back-office domain.

Specializes in IT planning, roadmap development for core system and legacy modernization, vendor sourcing, PKG implementation, and project management.

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.