NRI SecureTechnologies Economic Security Consulting Department Hironori Takagi , Yuki Hirayama

As efforts to develop practical applications for quantum computing proceed apace, the risk of breaches in conventional cryptographic technologies is becoming increasingly real. In order to maintain a safe and trustworthy digital society, a migration to next-generation cryptographic technology in the form of Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) will be essential. To learn more about the threats posed by quantum computing, international trends surrounding PQC, and the measures that companies should take, we spoke with NRI SecureTechnologies members Hiroki Takagi and Yuki Hirayama, who are well versed in this topic.

The risks of the ensuing quantum era and the limits of cryptographic technology

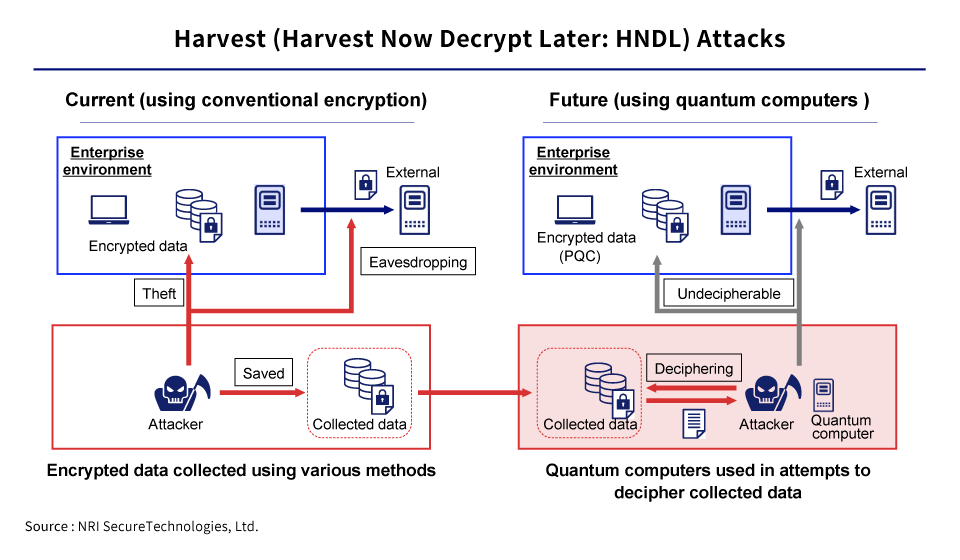

The threats posed by quantum computing are by no means entirely limited to future scenarios, either. Even at present, there have been strong indications concerning the danger of “harvest (Harvest Now Decrypt Later: HNDL) attacks”. This is a method by which attackers collect and store encrypted communications and data in the present, so that at some future point they can attempt to decipher that data once quantum computing has become viable. Any data that needs to be protected over the long term because of legal requirements, business constraints, or other such reasons could be targeted by such attacks, which means that countermeasures need to start being taken before quantum computing reaches the practical application stage.

Traditional encryption has to do with ensuring confidentiality, safety, authenticity, and non-repudiation, and it has bene broadly employed for communications, electronic signatures, financial transactions, and so forth. Some representative examples of this are symmetric key encryption (e.g., AES), public key encryption (e.g., RSA, ECDSA), and hash functions (e.g., SHA-2, SHA-3). Although these have provided ample security for conventional computers, the situation is different in the face of the computational power of quantum computing.

Symmetric key encryption and hash functions are able to ensure a certain degree of safety by extending key length or hash length. But with public key encryption like RSA, increasing the key length does nothing to enhance security, and it is thought that quantum computers will be able to decrypt the data in short order. In other words, an alternative to public key encryption will be essential in the quantum era, and traditional frameworks will not be able to keep our society safe.

The rise of PQC and an international migration roadmap

Currently, under the guidance of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), five types of approved algorithms have been defined under the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS), which serve as international standards for this technology. These are based on mathematical foundations such as lattice-based cryptography, code ciphers, and hashes, and are expected to be highly resistant to quantum computation.

In addition, various countries have come up with policies regarding PQC migration. In the US, the White House has announced that it has set a deadline to mitigate the security risks posed by quantum computing by 2035, and the National Security Agency (NSA) is requiring all national security-related systems to fully transition to PQC by 2033. These initiatives are still in the planning and consideration stage, but the NIST has also announced that the use of public key cryptography in principle will be discontinued by around 2035.

The EU has announced a policy all of its member states to migrate as fully as possible to PQC by 2035, with those states required to enact measures against high-risk applications by 2030. The UK and Canada are also aiming to make gradual transitions, with the plan being to migrate their high-priority systems by 2031, and to complete the transition of all other systems by 2035.

As for Japan, at the “Study Group on Deposit-taking Institutions' Response to Post-Quantum Cryptography” held in 2024, the discussion focused primarily on how financial institutions would migrate to PQC, and the Financial Services Agency (FSA) called on financial institutions to begin making the PQC transition immediately. Meanwhile, in terms of the national government overall, a plan was put forward at the Inter-Ministerial Committee convened in June 2025 to formulate a PQC migration roadmap that would enable government agencies to make the transition next fiscal year. Although no deadline for this migration has been clearly defined as of yet, it would appear that Japan is looking at the mid-2030s as a target period, in light of the trends happening in other countries.

PQC is no longer just a technological option — it is becoming an absolute requisite for maintaining social infrastructure.

Steps that companies should take, and challenges

- Collecting information and establishing a system

Build an organizational structure for identifying technological and regulatory changes and promoting migration. The key thing is for executive management to be involved and to perceive the relevant issues on a companywide scale. - Inventorying and selecting information assets and target systems

Identify the systems and data that your company possesses, and determine their levels of priority for migration. - Taking stock of cryptographic technologies (creating a crypto-inventory)

Visualize how your cryptographic technologies are being used. In addition to checking design documents and conducting on-site interviews, carrying out tool-based surveys is also effective. - Assessing migration priority levels

Taking a multi-faceted view that includes your information’s level of criticality and retention period, quantum-resistance, and migration costs, assess the necessity and level of priority for PQC migration of the systems being migrated wherever encryption is used. - Formulate a migration plan

Based on the assessment results, create a roadmap for achieving a staged PQC migration. - Execute the migration

In cooperation with external vendors, cloud providers, and various other stakeholders, carry out your system upgrades and implement your encryption switchover.

That being said, migration comes with a host of challenges. For example, migrating a large-scale system can require a great deal of time, and any increase in communication volume or computational volume could result in a heavier system load. Furthermore, there is a undeniable chance that your new algorithms could be compromised after the migration. A shortage of specialized personnel can also be a major constraint.

To deal with these challenges, the development of “crypto-agility”, which is the ability to flexibly and rapidly switch encryption methods, is vitally important as a basic policy when it comes to moving forward with a PQC migration. Achieving that requires a multifaceted and gradual effort that starts with the creation of a crypto-inventory, and also includes adopting a “hybrid system” combining existing methods and PQC, building an architecture that enables your company to conduct key management in a centralized manner, and moreover, enhancing linkages with external partners.

As for what comes after PQC, it is essential to come up with realistic plans and run ongoing verifications with these challenges and measures in full view. Another important thing is to secure the necessary personnel and budget over the long term, under the leadership of executive management.

Preparing for the quantum era

Across the world, efforts are predominantly underway to achieve this migration by the mid-2030s, and it is crucial for Japanese companies to begin taking such steps quickly. A realistic first step in this direction would be to begin by taking inventory of your information assets and cryptographic technologies, and then moving on to assess their levels or priority and come up with a plan.

Profile

-

Hironori TakagiPortraits of Hironori Takagi

NRI SecureTechnologies

Economic Security Consulting Department -

Yuki HirayamaPortraits of Yuki Hirayama

NRI SecureTechnologies

Economic Security Consulting Department

* Organization names and job titles may differ from the current version.